Tilopa: Master of Mahāmudrā & the Ganges Transmission

Oct 13, 2025

Tilopa was a mystic who lived in India around the 10th–11th century. He’s known as the first human master of the Mahāmudrā lineage, a teaching that reveals the natural, unconstructed state of the mind.

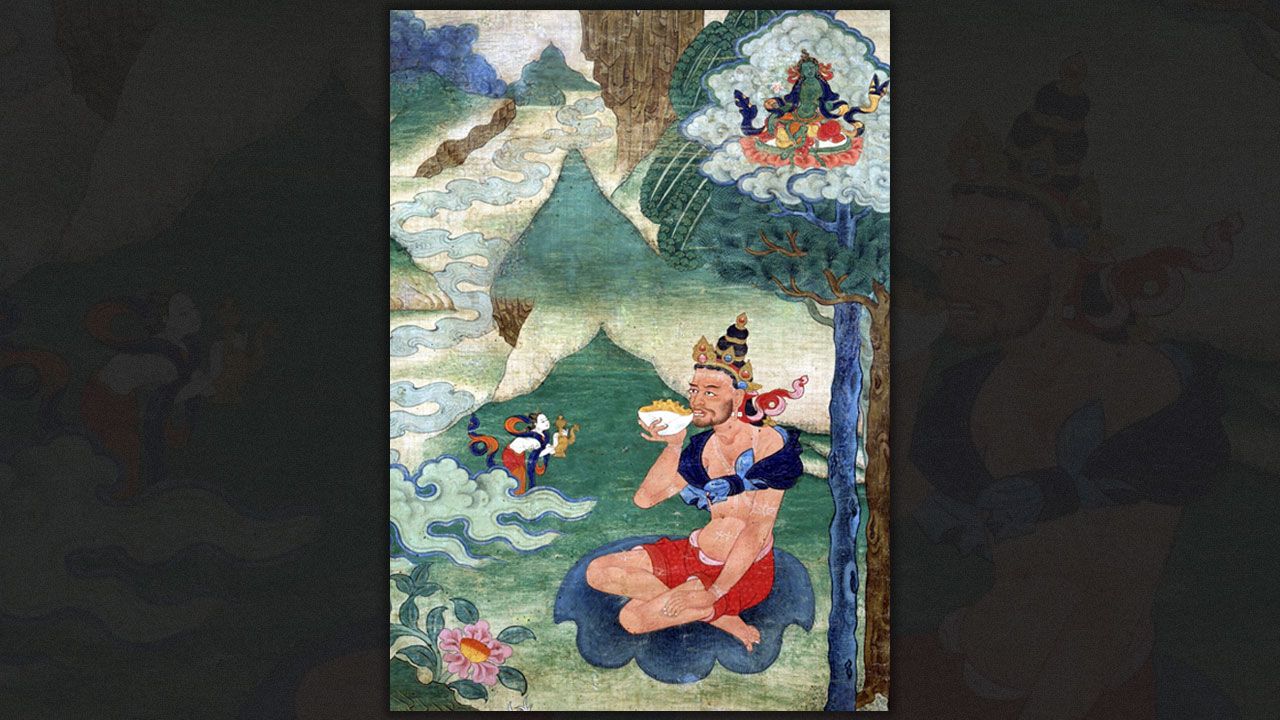

Tilopa worked as a sesame seed grinder and received his greatest teachings from dakinis, female embodiments of wisdom who appeared in vision and human form. Every detail of his life, from his humble labor to his ecstatic realizations on the banks of the Ganges, became a teaching in itself.

His student, Naropa, carried his transmission into Tibet, where it became the foundation of the Kagyu school, one of the four main lineages of Tibetan Buddhism.

In this article, we’ll dive into Tilopa’s life and the Mahāmudrā teachings that continue to guide meditators a thousand years later.

Tilopa & Tantra in 10th–11th Century India

Mahasiddha Tilopa was born in Bengal during the height of the Pāla Empire, a dynasty that ruled eastern India from the 8th to the 12th century. The Pālas were strong supporters of Buddhism, especially Mahayana and Vajrayana lineages, and their rule saw the construction and expansion of the great Buddhist universities, Nalanda, Vikramashila, Somapura, and Odantapuri. These centers were state-supported institutions with thousands of resident monks, structured curricula, and formalized systems of debate, scholarship, and tantric practice.

By the late 10th century, Vajrayana was fully embedded within Buddhist orthodoxy. Tantric deities like Hevajra and Chakrasamvara were incorporated into sādhanas taught inside these universities. Commentaries were copied and refined, while monks performed deity yoga and mantra recitation under strict monastic codes. Tantra was part of the official Buddhist curriculum.

But alongside the monasteries, another force had already been shaping Tantra for generations. The Mahasiddha movement, outside the walls, outside the caste structure, had been growing in the cremation grounds, the homes of outcastes, and in the solitude of wandering yogis. These siddhas received transmission through oral teachings, consort practices, and visionary encounters with dakinis.

Mahasiddha Tilopa's Origins

According to the Blue Annals, compiled by Gö Lotsawa Zhönnu Pel in the 15th century, Tilopa was born into a Brahmin family in Chittagong, eastern Bengal, and given the name Prajñabhadra. The text describes him as highly educated, trained in Vedic and Buddhist texts, and deeply familiar with both Brahmanical learning and Buddhist philosophy.

Marpa Lotsawa, the Tibetan translator and disciple of Naropa who preserved much of Tilopa’s oral legacy, records a different emphasis. In his biography of Tilopa, Marpa recounts that Tilopa “had no father or mother,” appearing suddenly in the world like someone “ripened by previous karma.”

Tilopa himself never clarified the matter. The ambiguity became part of his teaching. His life did not build upon a lineage. It dismantled the need for one. What followed were encounters that shaped him from within, yogis who gave direct instruction, dakinis who appeared in vision, consorts who initiated him through touch, through gaze, through command.

One of those figures was the dakini Matangi. Her instruction was simple, leave the monastery, grind sesame seeds by hand, and serve in the home of a courtesan. The task lasted for years. The name Tilopa, Tilo, sesame; pa, the one who works, came from this period.

The Twelve Years: The Wilderness Path of Embodied Realization

Tilopa used the word Mahāmudrā, “the Great Seal”, to name the unbroken reality he had entered. This seal was the natural clarity of mind itself, visible in every perception when nothing is being added to it. Every sensation, thought, and appearance arises within this space.

Mahāmudrā is the full expression of this view. It does not arise through elaboration, nor is it refined through reasoning. Tilopa stabilized this recognition during his twelve years in the wilderness. He gave that state to Naropa directly. He named what remains when all views and methods become transparent.

Tilopa’s Mahāmudrā begins where effort ends. It rests in a mind that is already free of fixation. The body may sit or move. Thoughts may appear. Emotions may pass through. Mahāmudrā does not resist these. It sees clearly that each one begins, displays, and dissolves within the same expanse.

Tilopa described this nature of mind in a way that left no space for speculation,

“The mind is like space, it has no shape, no color. It cannot be stained by good or bad.”

Core Principles of Tilopa’s Mahāmudrā

The core principles of Tilopa’s Mahāmudrā were received by Naropa and recorded in what became known as the Ganges Mahāmudrā, a series of verses spoken on the banks of the Ganges at the moment of final transmission. These verses were preserved in oral lineage, then translated into Tibetan and carried through the Kagyu school. The original source is a pith instruction (upadeśa) text, short, direct, and unembellished, designed to communicate realization, not analysis. What Naropa recorded reflects the mind-state he entered under Tilopa’s guidance.

“Don’t recall.”

The past has already moved. Recalling is the act of re-entering what is no longer present. When Tilopa gives this instruction, he is naming what happens when the mind looks backward. Attention moves away from what is alive. Memory may still arise, but there is no engagement. In Mahāmudrā, recognition happens now through resting where perception opens.

“Don’t imagine.”

Imagination creates a future that does not yet exist. It projects outcomes, seeks possibilities, and places attention on what has not arrived. Tilopa’s instruction points to immediacy. Resting attention is not drawn forward. It settles into contact with what is already here. Without imagining, the mind becomes quiet enough to observe what it is doing.

“Don’t think.”

Thinking is the motion of mind constructing itself. Tilopa is not speaking against thought. He is pointing to what appears before it. The simplicity of perception, the rawness of sound, breath, and sensation, comes before interpretation. Mahāmudrā remains with that level of contact. When thinking arises, it moves through awareness without forming identity.

“Don’t examine.”

Examination brings the mind into division. It begins sorting, judging, measuring. This is useful in knowledge-building. Tilopa is transmitting a way of seeing that does not depend on analysis. Mahāmudrā observes what arises without entering into separation. There is no distance between the observer and what appears.

“Don’t control.”

Control tenses the body and narrows awareness. The effort to control produces resistance. When control relaxes, the mind returns to its natural rhythm. Breath moves on its own. The senses open. Stillness appears without being made.

Ganges Mahāmudrā: Tilopa’s Final and Fiercest Instruction

Before Tilopa gave the Mahāmudrā transmission, Naropa had already spent years in search. He had been a celebrated scholar at Nalanda, trained in logic, philosophy, and ritual. But a dakini appeared and told him plainly:

“You understand the words, but not the meaning. Realization does not live in what you have mastered.”

She instructed him to find Tilopa, who had once worked as a sesame oil maker, integrating this humble work into his spiritual journey and teachings.

Naropa left Nalanda immediately. For twelve years he searched. When he found Tilopa, there was no welcome. There was no initiation. Tilopa gave no teaching. Instead, he placed Naropa into a series of twelve intense trials. Each hardship was designed to break his reliance on conceptual understanding, tests of devotion, surrender, physical endurance, and the loss of identity.

Naropa recounted,

“I have endured hardship. I have surrendered all constructs. I no longer carry theory.”

Only then did Tilopa speak. On the banks of the Ganges, he struck Naropa with his sandal, and Naropa entered a state beyond grasping. Tilopa then gave him a series of pith instructions, twenty-eight verses that encapsulated the essence of Mahāmudrā. These verses were spoken at the culmination of a transmission that had already taken root.

This became the Ganges Mahāmudrā, a direct record of recognition. Naropa later passed these verses to Marpa, who carried them into Tibet. The lineage began here.

The verses are precise. Each line carries the weight of a lifetime that no longer needed to hold anything.

“Pure space has neither color nor shape; it cannot be stained black or white. Likewise, the mind’s essence has no color or form; it cannot be sullied by good deeds or bad.”

Tilopa’s words dismantle the idea that the mind is a container, something that stores impressions, builds identity, or carries moral weight. When he says “pure space has neither color nor shape,” he’s pointing to the exact nature of awareness itself, ungraspable, unmarked, and incapable of being defined by content.

The mind’s essence isn’t shaped by thought, memory, trauma, or virtue. Those things appear in it, but they do not alter what it is. Just as the sky isn’t changed by clouds, awareness isn’t changed by what passes through it. Even intense emotional states do not leave a residue in the nature of mind. They arise, display, and dissolve. What remains is unchanged.

“A thousand eons of darkness cannot dim the crystal clarity of the sun’s heart; likewise, eons of saṃsāra cannot veil the clear light of mind’s essence.”

Mind does not wear out. Its clarity does not depend on duration, effort, or purification. Even lifetimes of wandering do not reduce its presence. Tilopa confirmed what is already intact.

“Gazing intently into the empty sky, vision ceases; likewise, when mind gazes into itself, the torrent of discursive thoughts ends and supreme enlightenment is gained.”

Looking inward reveals the stopping point of thought. The motion of the mind relaxes when no object is held. What opens is not absence, but vivid stillness. The kind that does not require maintenance. The kind that completes itself

“Be still and stay relaxed in genuine ease. Be quiet and let sound reverberate like an echo. Keep your mind silent and watch the end of all worlds.”

Tilopa taught resting without tension. A stillness that includes everything. Not the quiet of suppression, but the ease that arises when nothing is being managed. A silence that hears everything because it does not try to interrupt.

“Cut the root of the mind and let consciousness collapse into its source, and you attain Mahāmudrā.”

The origin of thought, when seen clearly, loses its power to divide. Cutting the root is not an act of violence. It is the moment awareness recognizes that it was never separate from itself.

“In the transcending of mind’s dualities is Supreme Vision; in a still and silent mind is Supreme Meditation; in spontaneity is Supreme Activity; and when all hopes and fears have died, the Goal is reached.”

These verses hold view, meditation, and fruition in one field. Not as parts to progress through, but as qualities of the same recognition. Each line describes how mind functions when it no longer divides what it sees.

“Have compassion for those who wander in saṃsāra… Adhere to a guru, for when his blessing touches your heart, mind is liberated.”

Tilopa's Life and Teachings on the Ganges Mahamudra

One of the most important modern presentations of Tilopa’s teaching is Tilopa’s Wisdom: His Life and Teachings on the Ganges Mahamudra, written by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche. The book is divided into two parts. The first follows the arc of Tilopa’s life, from his early Brahmin upbringing to his years of wilderness practice and the transmission of Mahāmudrā on the banks of the Ganges. It traces his meetings with key teachers like Saryapa, Lawapa, and Matangi, and shows how each instruction prepared him to stabilize the view he would eventually pass to Naropa.

The second part is a detailed commentary on the Ganges Mahāmudrā, verse by verse. Thrangu Rinpoche presents each line with clarity and depth, showing how the language of the teaching arises from Tilopa’s direct experience. He explains the relationship between awareness and thought, the structure of the mind’s natural luminosity, and the conditions in which recognition becomes stable.

From Nalanda Scholar to Begging Disciple

Naropa began as a scholar of exceptional rank. As a mahāpaṇḍita at Nālandā, he held a seat of intellectual authority, trained in Madhyamaka philosophy, logic, and tantric ritual. His mind could navigate the most complex texts and his speech could hold its ground in any formal debate. But realization had not touched him.

According to Marpa’s hagiographic transmission, Naropa endured twelve major hardships under Tilopa’s guidance. Other versions, such as those recorded in the Kagyu oral tradition and expanded upon by teachers like Thrangu Rinpoche and Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso, speak of twelve minor and twelve major hardships.

These hardships were designed to remove a specific layer of identification. From Marpa’s lineage account, the major hardships included,

- Leaping from a cliff at Tilopa’s command, shattering his body. Tilopa healed him with a touch.

- Jumping into a fire, confronting fear and bodily attachment.

- Stealing and consuming sacred offerings, collapsing moral rigidity.

- Constructing a bridge in a swamp full of leeches, testing endurance and selfless labor.

- Being told to strike a minister, a princess, and a prince, each time receiving beatings from the royal guard.

- Becoming attached to a consort, then witnessing Tilopa beat her, breaking the illusion of romantic fulfillment.

- Offering his own body as the center of a mandala, an act of total surrender without hesitation.

In several versions, Tilopa appears multiple times disguised, as a beggar, as a corpse, as a stranger, testing Naropa’s recognition and humility. Often, Naropa failed to recognize him and was turned away or scolded. Each encounter pressed him further out of habit and further into clarity.

Monasteries and Sacred Sites in His Name

Though Tilopa lived as a wandering yogi outside established monastic systems, his influence runs through nearly every Kagyu monastery in existence today. The Kagyu school, beginning with Tilopa’s direct transmission to Naropa, then to Marpa, Milarepa, and Gampopa became one of the four great traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Because of this, most Kagyu monasteries trace their spiritual heritage directly to him. A few sites are explicitly connected with his life and regarded as centers of pilgrimage and ongoing devotion.

Tilokpur Nunnery (Karma Drubgyu Thargay Ling) – Himachal Pradesh, India

Image Source: tnp.org

Built near a cave where Tilopa is said to have meditated for twelve years, Tilokpur is regarded as one of the most sacred living sites of the Tilopa lineage. The nunnery belongs to the Karma Kagyu tradition and sits above the Kangra Valley, facing the Ganges tributary that legend associates with Tilopa’s realization.

Daily practice here begins at dawn with Mahāmudrā meditation and mantra recitation, followed by rituals that recall Tilopa’s six pith instructions: Many nuns complete three-year solitary retreats modeled on Tilopa’s wilderness practice.

The site’s main temple holds a carved image of Tilopa seated cross-legged beside a mortar and pestle, the “sesame grinder,” a reminder of realization through humble, embodied work. Visiting practitioners often make prostrations at the mouth of Tilopa’s cave and circumambulate the rocky hill behind it, said to echo his footsteps.

Pharping, Nepal – The Yogin Caves and Kagyu Institutes

Several Kagyu monasteries in Pharping maintain shrines to Tilopa as the root holder of their lineage. Though Pharping is more widely known for its connection to Padmasambhava, Kagyu practitioners also regard it as a place where Tilopa’s realization energy is palpable.

Tilopa’s statue is enshrined in Karma Drubgyu Choling Monastery, where monks perform annual Ganges Mahāmudrā recitations. The Ganges Mahāmudrā Puja is chanted in the original Tibetan translation, accompanied by long horns and hand drums, symbolizing the union of emptiness and sound, a direct reference to Tilopa’s final teaching to Naropa.

Nearby retreat centers under Thrangu Rinpoche and the 17th Karmapa include Tilopa’s verses in their Mahāmudrā curricula, and students often undertake “Tilopa Week,” seven days of silent sitting and direct oral transmission of the Ganges verses.

Phyang Monastery – Ladakh, India

Founded in 1515, Phyang is one of the main Drikung Kagyu monasteries of Ladakh. The Drikung lineage traces its roots through Tilopa’s original transmission and keeps his image alongside Naropa and Marpa in the main assembly hall.

During the annual Phyang Tsedup festival, thangka banners of Tilopa, Naropa, and Milarepa are unfurled while monks enact ritual dances based on the Twelve Deeds of Tilopa. The festival’s centerpiece, the Naropa mask dance, dramatizes Naropa’s final meeting with Tilopa at the Ganges, Tilopa striking him with his sandal to awaken realization.

Rumtek Monastery – Sikkim, India

Rumtek, seat of the Karma Kagyu school and home of the Karmapa lineage, maintains Tilopa’s presence at the root of its lineage tree. Every Guru Puja begins with invocation to “the Lord of Siddhas, Tilopa,” followed by Naropa and Marpa.

During the annual Mahāmudrā Drubchen retreat, senior monks give oral commentary on the Ganges Mahāmudrā verses. Young monks learn the history of Tilopa’s life and the symbolism of his sesame oil practice.

Tilopa Quotes

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the six rules of Tilopa?

They are Tilopa’s final instructions to Naropa, recorded in the Ganges Mahāmudrā: “Don’t recall. Don’t imagine. Don’t think. Don’t examine. Don’t control. Rest.” Each line stops habitual mind movement and brings awareness into direct, unconstructed presence. These six became the foundation for Mahāmudrā practice.

Why does Tilopa hold a fish?

The fish refers to Tilopa’s early life as a tantric practitioner under the dakini Matangi, who instructed him to leave monastic life, grind sesame seeds, and live among common people. In some accounts, he worked in a brothel preparing fish. The image represents realization born through contact, labor, and instruction outside religious structure.

What is the lineage of Tilopa?

Tilopa gave Mahāmudrā to Naropa. Naropa passed it to Marpa, who trained under him in India for twelve years. Marpa gave it to Milarepa, who practiced in Himalayan solitude until realization stabilized. Milarepa passed it to Gampopa, who merged it with the Kadampa monastic tradition. This forms the Kagyu lineage.

Who is the reincarnation of Tilopa?

There is no recognized reincarnation lineage for Tilopa. His teaching continues through direct transmission of view, not formal succession. Lineage holders are those who enter and stabilize Mahāmudrā, not those enthroned in his name.

Who is Tilopa in Buddhism?

Tilopa (988–1069 CE) is the first human holder of the Mahāmudrā lineage in the Kagyu tradition. He was trained by yogis, consorts, and dakinis, practiced outside institutional systems, and transmitted the essence of realization through direct contact. His teachings form the core of Tibetan Vajrayāna’s most experiential path.

What is the story of Naropa and Tilopa?

Naropa, a scholar at Nālandā, was told by a dakini: “You understand the words, but not the meaning.” He left everything to find Tilopa, who gave him no teachings, only twelve brutal trials. After Naropa’s identity collapsed, Tilopa transmitted Mahāmudrā in twenty-eight verses. This moment birthed the living lineage.