Sir John Woodroffe (Arthur Avalon): The Jurist Who Gave the West Tantra

Sep 02, 2025

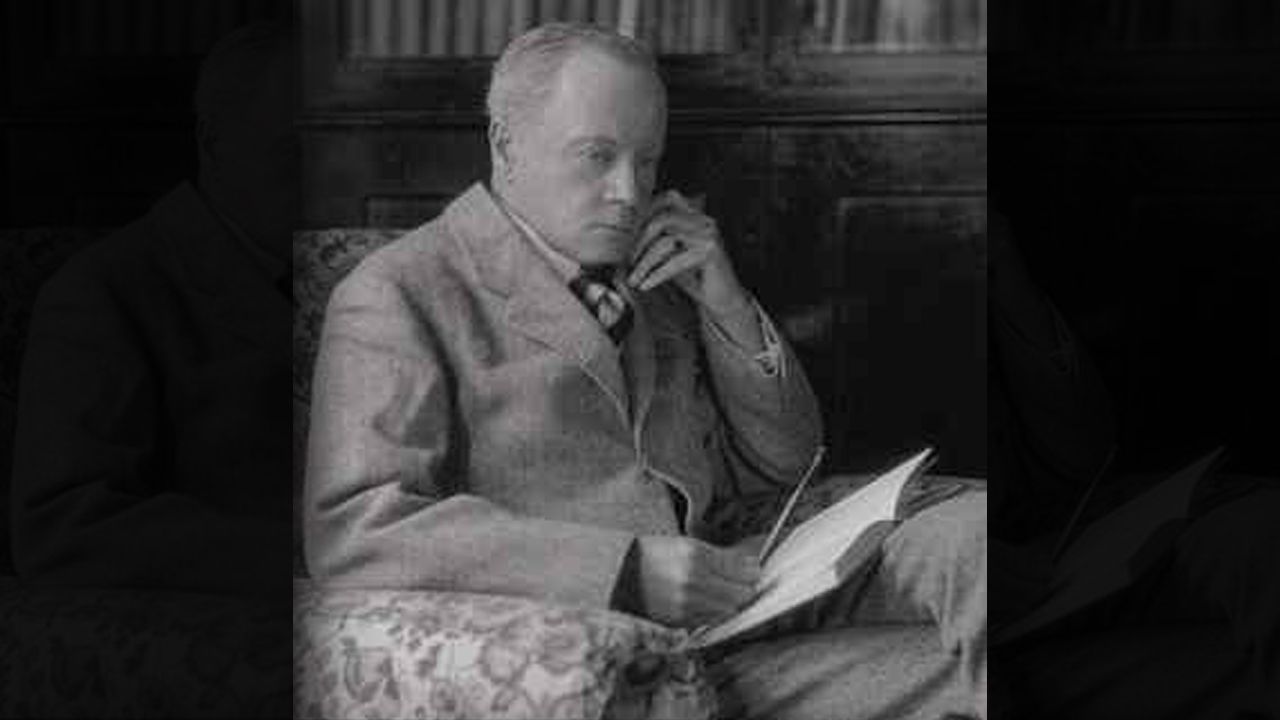

John Woodroffe was the Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court and one of the British Empire’s top legal minds in India. Under the pseudonym Arthur Avalon, he became the first Western scholar to rigorously translate and practice the original Tantric texts offering the English-speaking world its first real access to Kuṇḍalinī, cakras, mantra, and Śakti as living systems of practice.

His 1919 book The Serpent Power was the first detailed Western guide to the chakra system as it actually appears in the Tantras. Woodroffe is a large part of the foundation of how most of the West understands Tantra today.

From London to Calcutta

Sir John George Woodroffe was born in Calcutta in 1865 to James Tisdall Woodroffe, then serving as Advocate-General of Bengal. His maternal grandfather was James Hume, a Scottish judge who had served on the Supreme Court of Calcutta. From both sides, he inherited a powerful legal lineage deeply embedded in the British colonial system. From birth, he belonged to the top legal echelons of the British Empire in India.

His father sent him to England for education, where he attended Woburn Park School and later Brasenose College, Oxford, graduating with honors in jurisprudence. He also passed the civil law examinations, which were essential for his legal career.

In 1889, he was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple, and in 1890, he returned to Calcutta and joined the Indian Bar. By 1902, he was appointed Standing Counsel to the Government of India. In 1904, he became a Puisne Judge of the Calcutta High Court, and in 1915, he was elevated to Chief Justice. He was recognized for his expertise in civil procedure, notably through his influential commentary on Act V of 1908. He also held the position of Tagore Law Professor at Calcutta University, where he lectured on Hindu law. Throughout his legal roles, Woodroffe demonstrated a deep engagement with Indian law and played a significant part in its interpretation and development during the colonial period.

All his appointments and publications during this period were under the name James T. Woodroffe.

A Legal Mind Drawn to Sanskrit Studies

In 1907, Sir John Woodroffe was presiding over a criminal trial in Calcutta when something unusual occurred. The defendant, a Tantric ascetic, had been accused of using abhichāra, ritual sorcery, to interfere with the proceedings. During the session, Woodroffe reportedly experienced a sudden, unexplained mental blankness. Witnesses said he paused mid-questioning, unable to concentrate. The sensation lifted only after the sadhu was escorted out of the courtroom. Later, Woodroffe was told the ritual used was a form of spellwork intended to suspend mental function.

Most officials in his position would have dismissed it, but Woodroffe began privately researching Tantra, focusing on the Śākta schools of Bengal, which emphasized the worship of Śakti and the disciplined awakening of Kuṇḍalinī. What began as legal curiosity became direct study. He learned Sanskrit to read the primary Tantras with accuracy.

Through contacts in Calcutta’s legal-academic circles, he was introduced to Pandit Shivachandra Vidyārṇava Bhattacharya, a renowned Kaula Tantric and author of Tantratattva. Woodroffe requested instruction. Shivachandra accepted, and initiated him into the Kaula lineage . From that point forward, Woodroffe practiced daily. He performed ritual (pūjā), recited mantras, memorized ślokas, and worked internally with breath and visualization as prescribed in the texts.

By the time Woodroffe retired from the bench in 1915, he had completed a body of translations and commentaries that introduced core Tantric texts to English readers for the first time. That foundation would eventually become The Serpent Power.

Avalon Appears: An Introduction to Tantra

Sir John Woodroffe began publishing his translations of Tantric texts in 1913 under the name Arthur Avalon. According to his biographer Kathleen Taylor, the name was inspired by The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon, a Pre-Raphaelite painting by Edward Burne-Jones. In the image, King Arthur lies in stillness, surrounded by silent female figures, awaiting his return. For Woodroffe, it was metaphor. Tantra, like the sleeping king, had not disappeared. It was resting. Waiting. Intact, but hidden.

The name Avalon gave Woodroffe the freedom to publish what his public role as Chief Justice would never have allowed. It also carried his intention clearly, to reawaken a wisdom that was still alive, just unseen.

Woodroffe was still serving as a High Court Judge in Calcutta when his early works were released. Publishing under his real name could have cost him his legal career, or worse, discredited the texts he had worked so hard to translate. Colonial institutions, after all, regarded Tantra as obscene, irrational, or at best, irrelevant. The name Avalon gave him the freedom to operate across both worlds, as he could move between courtrooms and cremation grounds, between university lectures and underground cakra sādhana.

However, the name Avalon wasn’t Woodroffe’s alone. His Tantric scholarship was deeply collaborative, and the name masked not just one man but a circle. His closest ally was Atal Bihari Ghose, an Indian lawyer and Sanskrit scholar from a devout Śākta background. Ghose was a co-translator, a guide, and a bridge into the living traditions of Bengal Tantra. Together, they studied under Shivachandra Vidyārṇava Bhattacharya, a revered Kaula guru and author of Tantratattva. The guru’s swadeshi politics, which leaned anti-colonial, didn’t stop him from initiating a British judge into the lineage.

With Ghose and other Indian scholars, Woodroffe formed a working group that operated in private, outside the gaze of both the colonial government and orthodox Hindu society. They translated over twenty Sanskrit texts, including Mahānirvāṇa Tantra, Tantratattva, and the Ṣaṭcakra-nirūpaṇa, each with rigor, and often with reverence. The name “Arthur Avalon” became the shared signature of their efforts, it was a protective boundary around sacred transmission.

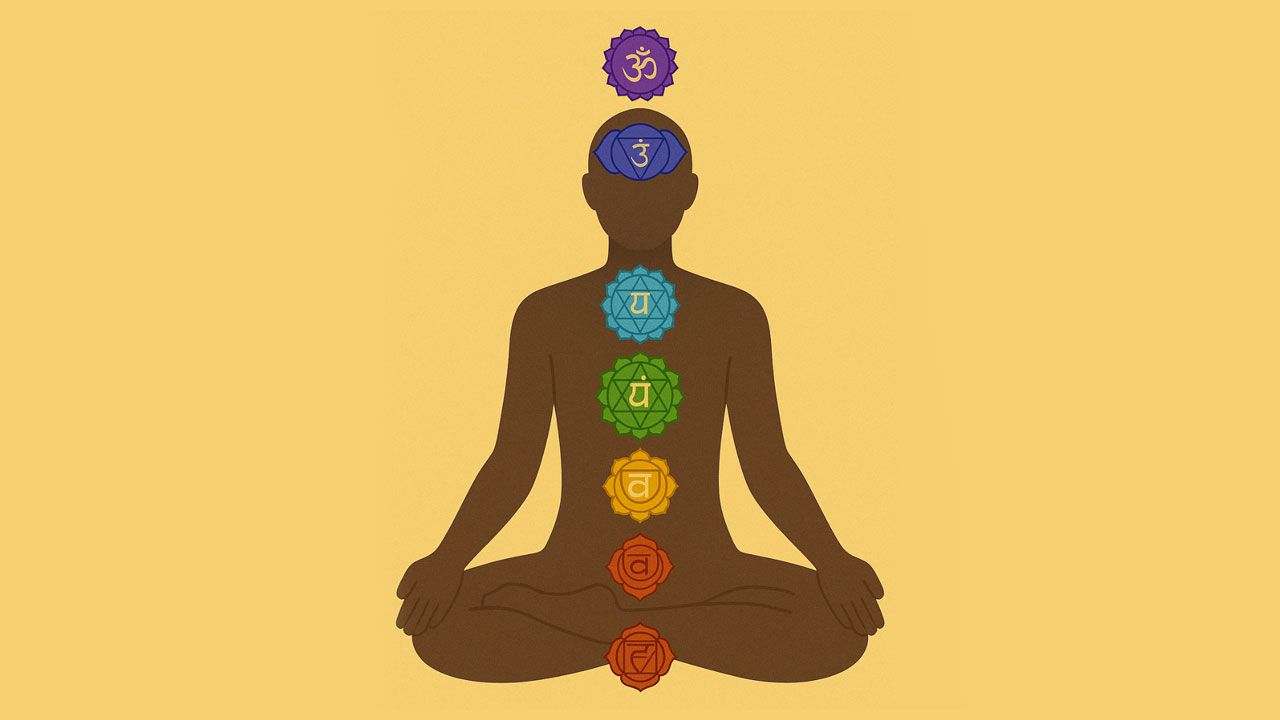

The Six Cakras and the Crown: Embodied Maps of Awakening

For Woodroffe, each chakra operated like a coded interface between physical tissue, psychic force, mantra, and liberation. He emphasized the granular architecture of these centers, down to the shape of yantras, the direction of triangles, the role of śaktis, and the vibrational effect of seed syllables on the nervous system.

1. Mūlādhāra

Located just above the perineum, Mūlādhāra is a four-petaled red lotus containing the syllables vaṁ, śaṁ, ṣaṁ, and saṁ. At its core is a yellow square, the geometric form of the Earth element (pṛthvī tattva), and inside this square lies the svayaṁbhū liṅga, the “self-arisen axis” of subtle force. Around this axis, Kuṇḍalinī Śakti is coiled three and a half times. She is not asleep. She is deliberately bound, restrained at the root until the practitioner is ready to initiate her release.

“Kuṇḍalinī is power (Śakti). All that moves, breathes, and lives does so because of Her. In the unawakened, She lies at rest in Mūlādhāra. She is not inert. She is potential itself.” (The Serpent Power, p. 8)

This center, for Woodroffe, contained biological force, ancestral patterning, karmic latency, and the entire potential for liberation, but compressed into density. The square within the lotus marks the inertia and structural resistance that must be metabolized before any energy can ascend.

He stressed that the practitioner must learn to stabilize attention, regulate sexual energy, and engage Laṁ, the seed sound of Earth, to vibrationally unlock the entrance to the suṣumṇā, the central channel. It’s physically felt as pressure at the perineum, heat in the pelvic floor, or a dense stirring at the base of the spine.

Woodroffe referenced Dākinī Śakti, the fierce guardian of this center as an internal force that actively prevents ascent until readiness is achieved. She is stationed there to protect the nervous system from premature access to higher voltages of prāṇa.

“The ascent of Kuṇḍalinī is not permitted until the lower Tattvas are made pure. Dākinī stands at the gate to ensure this law is obeyed.” (The Serpent Power)

2. Svādhiṣṭhāna

Located just above Mūlādhāra, in the region of the reproductive organs, Svādhiṣṭhāna is a six-petaled vermilion lotus. Each petal is inscribed with one of the syllables: baṁ, bhaṁ, maṁ, yaṁ, raṁ, laṁ. These varṇas represent distinct energetic patterns connected to sexuality, emotional reactivity, and residual impressions from past experience.

At the center of the lotus is a silver crescent moon, the geometric marker of the Water element (apas tattva). It rests on a makara, a mythical aquatic creature symbolizing movement beneath the surface of awareness. The bīja mantra is Vaṁ, and its function is to regulate the energetic instability of this center through vibration and breath.

Woodroffe emphasizes that this chakra holds the vāsanās, the unconscious drives and emotional patterns that influence behavior without awareness. They shape how the practitioner experiences desire, shame, arousal, and attachment. Unless addressed, they interfere with concentration and cause mental scattering:

“It is in this centre that the impressions (saṁskāras) lie, particularly those that are connected with desire. Until they are stilled, the mind remains reactive and unstable.” (The Serpent Power)

The presiding deity is Viṣṇu, who sustains the internal cohesion of the Water element. In the yogic process, this means stabilizing the patterns of emotional and sexual energy so they do not spill over into mental distraction or physiological depletion. Viṣṇu maintains containment while transformation is underway.

Rākiṇī Śakti governs the active regulation of this center. She presides over the transformation of sexual force and stored emotional memory. Woodroffe describes her as “nourished by the nectar which exudes from the Moon” (The Serpent Power, p. 113), referring to the subtle bindu that descends from higher centers. She ensures that the system is prepared to handle the energetic intensity of further ascent. If the contents of Svādhiṣṭhāna are not metabolized, Rākiṇī prevents progression.

“When Kuṇḍalinī leaves Mūlādhāra and reaches the Svādhiṣṭhāna, the Yogi trembles, and his mind becomes free from lust.” (The Serpent Power, verse 10)

3. Maṇipūra

Located behind the navel and aligned with the solar plexus, Maṇipūra means “city of jewels.” It is described by Woodroffe as a ten-petaled lotus, each petal marked with one of the syllables, ḍaṁ, ḍhaṁ, ṇaṁ, taṁ, thaṁ, daṁ, dhaṁ, naṁ, paṁ, phaṁ. These represent forces tied to digestion, assertiveness, anger, and the power to act. The element is Fire (tejas tattva), and its bīja mantra is Raṁ, the vibratory trigger that awakens internal heat and transformation.

At its center lies a downward-pointing red triangle, seated on a ram, the vāhana of Agni, the fire deity. For Woodroffe, as someone initiated into the Kaula lineage, he treated Maṇipūra as the true furnace of the subtle body, the point where the latent residues of fear, control, and egoic striving must be burned. He explained this triangle as the core generator of upward force:

“This is the centre of will, of inward digestion, and of the force which, when awakened, dissolves emotional residue and drives upward motion.” (The Serpent Power)

Here, Woodroffe saw the energetic consequence of both emotional repression and impulsivity. Without clarity, the fire becomes volatile. With regulation, through breath, kumbhaka, mantra, and inner attention, it stabilizes into discipline. In his practice, Maṇipūra was a test. He noted that many practitioners become stuck here, clinging to control, mistaking intensity for insight, or forcing ascent without internal readiness.

The presiding deity is Rudra, who burns away illusion and reactive will. His Śakti, Lākinī, is stationed here to oversee the purification process. Woodroffe described her as both fierce and exacting, ensuring that only integrated force moves beyond this point. She governs the ethical clarity of power, containment.

When Kuṇḍalinī pierces this center, the yogi experiences distinct physical and mental shifts. Woodroffe recorded it plainly:

“When She leaves this Lotus, the Fire of the belly subsides, and the mind grows still, no longer agitated by pride or will.” (The Serpent Power, verse 11)

4. Anāhata

Located behind the heart center, Anāhata means “unstruck” or “unstruck sound”, a vibration that arises from the inner pulse of consciousness itself. It is depicted as a twelve-petaled lotus, marked with the Sanskrit syllables kaṁ, khaṁ, gaṁ, ghaṁ, ṅaṁ, caṁ, chaṁ, jaṁ, jhaṁ, ñaṁ, ṭaṁ, ṭhaṁ. These syllables encode emotional memory, breath, sound perception, and the power of subtle resonance. The element is Air (vāyu tattva), and the bīja mantra is Yaṁ.

At the center is a gray hexagram, made from two interlocking triangles, one rising, one descending, indicating the union of Śakti and Śiva in the subtle body. For Woodroffe, Anāhata was the seat of breath, nāda (inner sound), and the first experience of deep-centered witnessing.

“This Lotus is the inner organ (antaḥkaraṇa), the meeting place of upward prāṇa and downward apāna. Here, desire and impulse are stilled by breath regulation, and the mind becomes fit to hear the Anāhata Nāda.” (The Serpent Power)

Woodroffe's practice and translation consistently returned to this point as the heart of subtle transformation. In his Kaula training, this cakra was where perception began to detach from the reactive mind and locate itself in a calm witnessing presence. The presiding deity is Īśa, a serene aspect of Śiva, and the Śakti is Kākinī, yellow and luminous, seated on a red lotus. Her role is to ensure the breath is purified before subtle perception is permitted. If the breath is irregular, the nāda remains unheard.

Woodroffe insisted that without stabilization here, higher ascent distorts. This center is cultivated through slow breath, mantra repetition, and internal listening. The yogi must learn to feel sound internally before rising further.

“When She leaves this Lotus, the Yogi hears the inner sound (nāda) clearly, and the senses turn inward. External identity begins to fall away.” (The Serpent Power, verse 12)

5. Viśuddha

Located at the base of the throat, Viśuddha means “purification.” It is a sixteen-petaled lotus, each petal bearing one of the Sanskrit vowels: aṁ, āṁ, iṁ, īṁ, uṁ, ūṁ, ṛṁ, ṝṁ, ḷṁ, ḹṁ, eṁ, aiṁ, oṁ, auṁ, aṁ, aḥ. The bīja mantra is Haṁ, and the element is Ether (ākāśa tattva), the first subtle field that transcends weight, friction, and gravity.

John Woodroffe described this cakra as the gateway of resonance and sound, where the internal rhythm of the breath becomes speech and mantra gains audible power. For Woodroffe, who translated and practiced mantra daily, Viśuddha was a center of vocalization, and the vibrational intelligence that conditions all perception beyond the senses.

“Here, the nāda becomes manifest as sound. The Yogi, having passed beyond breath and form, begins to refine subtle thought into articulate expression.” (The Serpent Power)

At its center is a white circle, resting on an elephant symbolizing knowledge and gravity of speech. The presiding deity is Sadāśiva, the eternal witness, unmoving, vast, and aware. His Śakti, Śākinī, is five-faced and luminous, holding bow, arrow, trident, and drum, indicating her role in clarifying all modes of sound, gross, subtle, mental, and causal. Together, they oversee the purification of expression, memory, and inner sound.

For Woodroffe, this was the seat of mantra-siddhi, the place where vibrational power becomes precise, effective, and reliable. Without Viśuddha refinement, sound remains diffuse. With it, sound becomes a weapon of clarity. He linked this directly to Yogic restraint, correct breath control (prāṇāyāma), silence (mauna), and repetition (japa) become essential here.

“When She leaves this Lotus, the Yogi hears no outer sound, only the clear internal nāda. Space itself appears contained. Speech ceases, but understanding deepens.” (The Serpent Power, verse 13)

6. Ājñā

Located between the eyebrows, Ājñā means “command” or “authority.” It is a two-petaled lotus, each petal bearing a powerful syllable: Haṁ and Kṣaṁ. For Woodroffe, they encode the full arc of mental function: Haṁ as the seed of prāṇa (life-force), and Kṣaṁ as the synthesis of all sound and dissolution of form. The bīja mantra Oṁ is often associated here, encapsulating both the manifest and the unmanifest.

Ājñā was described by Woodroffe as the seat of the subtle mind, where visualization, intuition, and directed will converge. It is a precision center for concentrated attention. For those trained in Tantric sādhana, it is where internal vision becomes stable, and where the inner teacher (antar-guru) reveals itself.

“In this Lotus, the mind is made steady. Distraction ceases, and the Yogi begins to see with the eye of pure knowledge.” (The Serpent Power, commentary on verse 14)

At its core sits the luminous form of Parama Śiva, the formless witness, and his Śakti, Hākinī, white, six-faced, holding the symbolic tools of higher perception. Woodroffe emphasized that the actual experience of this center was essential. Without stillness here, visualization remains unstable, and deeper meditative absorption (samādhi) is out of reach.

Woodroffe taught that Kuṇḍalinī’s entry into Ājñā marks the moment when dualistic perception begins to dissolve. Breath becomes fine. Thought becomes transparent. Identity no longer localizes in the body or mind.

“When She leaves this Lotus, the mind ceases to function in dualities. The Yogi rests in a field of radiant intelligence, no longer compelled by desire or memory.” (The Serpent Power, verse 14)

7. Sahasrāra

Sahasrāra, the “thousand-petaled” lotus at the crown of the head, is not counted among the six chakras. Woodroffe made this explicit. It is not a wheel (cakra) like the others. It has no element, no bīja mantra, and no fixed structure for activation. It is the termination point of the ascent, not a step within it.

He described it as the seat of Śiva, pure awareness, and the place where Śakti, having ascended through all previous centers, merges completely with consciousness. In Sahasrāra, dual function ends. There is no breath regulation, no mantra repetition, no visualisation. Practice stops. Union occurs.

“The Sahasrāra is the Abode of Liberation (Mokṣa). When Kuṇḍalinī reaches this Lotus, all dualities dissolve, and the Yogi ceases to function as separate mind or body.”

(The Serpent Power)

The lotus itself is formed by fifty Sanskrit syllables repeated twenty times, making 1,000 varṇas arranged in concentric circles. Each syllable represents a refinement of sound and subtle perception, but in Sahasrāra, even these fall away. Mantra no longer activates, but dissolves instead.

What remains is stillness. When Kuṇḍalinī enters this center, there is no further ascent. The process is complete. Woodroffe translated the experience directly:

“Having reached this Lotus, She dissolves in the Bliss of Union. All motion ends. All effort ceases. The Yogi abides in the state of eternal liberation.” (The Serpent Power, verse 15)

Beyond The Serpent Power: Woodroffe’s Other Works

While The Serpent Power is Woodroffe’s most recognized work, his contributions to the practical aspects of study and practice of Tantra extend far beyond this singular text. His other publications delve into the intricacies of mantra, the philosophy of power, devotional hymns, and the principles of Tantric practice.

The Garland of Letters: Studies in the Mantra-Śāstra

In this work, Woodroffe explores the significance of Sanskrit letters and their role in Tantric practice. He elucidates how each syllable embodies specific energies and deities, emphasizing the importance of mantra in spiritual transformation. This text serves as a comprehensive guide to understanding the phonetic and metaphysical dimensions of Sanskrit letters.

The World as Power

Here, Woodroffe examines the concept of Śakti (power) as the dynamic aspect of the Absolute (Brahman). He articulates how the universe is a manifestation of this power, offering insights into the interplay between consciousness and material existence.

Hymn to Kali: Karpūrādi-Stotra

This translation and commentary on a hymn dedicated to the goddess Kali provide a detailed analysis of her fierce and compassionate aspects. Woodroffe explores the symbolic meanings of the hymn's verses, shedding light on the transformative power of Kali worship. The text delves into the mythology, symbolism, and rituals associated with Kali, offering readers a profound understanding of her role in Tantric practice.

Principles of Tantra, Part II

As a continuation of his earlier work in Serpent Power, this volume delves deeper into Tantric philosophy and practice. Woodroffe discusses various rituals, the role of the guru, and the significance of Śakti.

Sound and Form: Tantra’s Language of Power

One of John Woodroffe’s most important contributions in The Serpent Power was showing that the chakra system is linguistic. Each center is constructed from sound. He drew this material directly from the Ṣaṭcakra-nirūpaṇa, a Sanskrit manual of yogic anatomy he translated and annotated in full, and treated it as a technical map of the body’s subtle architecture.

Mantras, in this system, are syllables, varṇas, each with a measurable effect on perception and physiology. Woodroffe emphasized that every mantra is a carrier of Śakti, designed to stimulate prāṇa, direct it along the spine, and support the ascent of Kuṇḍalinī. He wrote, “Mantras are the means by which the Supreme Śakti is led to unite with Śiva.”

Each chakra, as Woodroffe translated it, contains a single bīja mantra, a seed sound that governs its function, and a ring of phonetic petals inscribed with individual Sanskrit syllables. Woodroffe explained them as functional keys, passed down through Tantric lineages and tested through embodied practice. He also made the phonetic mapping visible. In his annotations to the Ṣaṭcakra-nirūpaṇa, he listed the exact syllables assigned to each cakra.

Chakra Petals and Syllables (based on Woodroffe’s translation)

| Chakra | Sanskrit Name | Petal Count | Petal Letters (Sanskrit syllables) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Root | Mūlādhāra | 4 | vaṁ, śaṁ, ṣaṁ, saṁ |

| 2.Genital | Svādhiṣṭhāna | 6 | baṁ, bhaṁ, maṁ, yaṁ, raṁ, laṁ |

| 3.Navel | Maṇipūra | 10 | daṁ, dhaṁ, naṁ, taṁ, thaṁ, daṁ, dhaṁ, naṁ, paṁ, phaṁ |

| 4.Heart | Anāhata | 12 | kaṁ, khaṁ, gaṁ, ghaṁ, ṅaṁ, caṁ, chaṁ, jaṁ, jhaṁ, ñaṁ, ṭaṁ, ṭhaṁ |

| 5.Throat | Viśuddha | 16 | All 16 Sanskrit vowels: aṁ, āṁ, iṁ, īṁ, uṁ, ūṁ, ṛṁ, ṝṁ, ḷṁ, ḹṁ, eṁ, aiṁ, oṁ, auṁ, aṁ, aḥ |

| Brow | Ājñā | 2 | haṁ, kṣaṁ |

| 7.Crown | Sahasrāra | 1000 | Formed by 50 letters × 20 circles |

John Woodroffe Quotes

Conclusion

John Woodroffe was a British High Court judge, a legal scholar, and the first Westerner to bring the original Tantric texts into public view with accuracy and respect. Under the name Arthur Avalon, he translated over twenty Sanskrit texts, practiced daily under an initiated teacher, and treated Tantra as a working system for awakening through the body.

His legacy matters because most of what we think we know about Tantra today still comes from his work, directly or indirectly. Without Woodroffe, there would be no chakra charts, no modern kundalini yoga, no Western access to śāstra-based practice.